An organization can never become truly Agile until it creates an overall enterprise architecture that is specifically designed to be Agile.

“Any organization that designs a system (defined more broadly here than just information systems) will inevitably produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.”—Melvin Conway

Dwell on that thought for a moment. It was included as part of Melvin Conway’s 1968 article How Do Committees Invent? in which Conway introduced the arguments and rationale for the concept that would become known as Conway’s Law. According to Conway’s Law, any system an organization designs and implements—including but not limited to IT systems—will necessarily be a reflection of that organization’s incumbent communication structure. To a long-time enterprise architect and systems designer this is not a revelation. Any practicing software architect recognizes this phenomenon and has undoubtedly attempted to decouple the link between organizational structures and processes, and the architecture of systems and software with varying degrees of success. The recognition of Conway’s Law as an impediment to effective architecture and design has caused architects to develop mitigating techniques over the years. However, the advent of Agile principles as its own discreet design, development, and sustain ecosystem has brought Conway’s Law back into the light of day. And the reason for this is at once simple and complex: An organization can never become truly Agile until it creates an overall enterprise architecture that is specifically designed to be Agile.

Current State

The conundrum that is Conway’s Law has been at least partly responsible for the current state of IT in many if not most organizations. Tasked with designing, implementing, and sustaining new technologies and functionalities, IT divisions have continually rowed against the current of imbedded organizational communications structures and the infrastructures they’ve spawned. That doesn’t let IT off the hook for suboptimal systems and support, but it does start to answer the complaints and questions that many business customers still have with, and pose to IT: Why is it taking so long? Why does it cost so much? Why doesn’t it work the way I want it to? It’s an all too familiar list.

And it’s precisely that myriad of issues that organizations have with IT performance that has created any number of “this time for sure” fixes over the years. From client/server to system-oriented architecture and everything in-between, the list goes on. All of these were “opportunities” to make IT and the solutions they produce better. Over the years those IT course corrections took many forms. The first impulse for many organizations was to reorganize IT and to focus on whatever the most modern processes were. Another reaction was to recruit different kinds of skill sets and employ different forms of management practices as a way to shake up IT and improve its performance. And still other reactions took the forms of embedding business knowledge inside of IT organizations or creating physical spaces for IT and business to collaborate more directly and effectively. These were all well and good so far as they went, and some approaches even led to improvement, but none of them addressed the issue raised by Melvin Conway.

The Agile Vision

With the advent and subsequent rise in popularity of the Agile software development methodology over the last decade, many organizations embraced this new, next solution to their business technology issues and complaints. But just like the many software trends and solutions that preceded it, just “doing” Agile was and is not enough to remedy the underlying problems identified by Conway’s Law. In a typical Agile implementation, there is much initial excitement over the methodology and the promises it brings. However, that excitement starts to dissipate once the newly formed Agile teams begin to realize that despite the new processes they cannot seem to move as quickly as they’d like. This all too common occurrence points to the problems in the underlying architecture of the organization. That’s why it is not sufficient to introduce new processes without recognizing and addressing the deep connection between an IT organization and its processes, and the architecture of its systems and software. Doing so repeats a mistake that just won’t seem to go away.

The proper corrective for this in the context of Conway’s Law is to align an Agile software development approach with an Agile enterprise architecture. Neither can be fully leveraged without the other. Neither can be fully successful without the other. And in the end, neither will help IT in supporting and facilitating the business goals and objectives of the overall organization without the other. Given that, what is the approach for accomplishing this once and for all?

First, acknowledge the fact that aligning an Agile software development process with an Agile enterprise architecture will be difficult. It will require behavior and software modifications and will take time, especially the behavior part. Remember, the ultimate goal here is to have the process structures and the software structures mimic each other conceptually. This goal is far from the reality of most IT divisions in most organizations. Most incumbent legacy IT systems are monolithic and tightly integrated, the very opposite of what Agile prescribes. The following is a quick look at what complimentary Agile structures might look like:

- An Agile software development organization typically consists of small (around 7 people), cross-functional and largely independent and empowered teams.

- To be independent these teams should each own certain components of the overall IT software landscape and work rapidly on adding and improving functionality to the components they own based on the prioritized business needs.

- In order for the Agile teams to be mostly independent and to move rapidly, the software components they own should lend themselves to such processes by mimicking an Agile approach.

- In other words, the software systems should also be composed of relatively small and largely independent software components.

The challenge of course is getting there, but the long-term payoffs can be substantial in terms of effective and efficient software and process structures that can stand the test of time through flexibility and adaptability.

The Reality Problem

As mentioned, recalibrating to a truly Agile ecosystem (software, process, and structure) is a non-trivial exercise. The challenges are many, particularly given the state of the aforementioned at most organizations in almost any industry.

Systems: The incumbent systems at many organizations can be generally described as dated, monolithic in size and scope, expansive with lots of add-ons, and in fairness, with a wealth of functionality that supports the operations of the business on a daily basis. That’s why they (still) exist. This type of system approach has not changed in a number of decades nor through several iterations of technology and methodology approaches. As modern computing emerged, and companies built their own systems, they skewed toward tightly coupled and dependent systems that were easier to develop and maintain. The advent of larger and more sophisticated mainframe infrastructures only accelerated this process by providing more computing and storage capacity to support the growth of these large software systems. This paradigm continued as companies began to rely more on software solution providers for their required functionality. The solution providers simply built for the existing infrastructures at most companies, making it easier to sell and support their products. Even the advent of more modern distributed and web-based systems and solutions did not change this development approach

Databases: The need for large centralized databases that could handle the data required and produced for these large systems drove the development of hierarchical and relational tools and products. This fed the monster so to speak, as those large databases became the repository for all of the add-on functionality that was bolted onto these systems over the years. Even when smaller and more discrete systems were implemented they still tended to use the incumbent database as its repository, adding to the growth and unwieldiness of a company’s overall database infrastructure.

Integrations: Out of necessity integration points for these large systems and infrastructures were designed to favor real-time calling between system components (services, APIs, etc.) which results in tight coupling and excessive dependencies between systems. Solution providers and hardware manufacturers doubled-down on this approach, creating the kinds of systems and infrastructures that grew exponentially to support this computing paradigm.

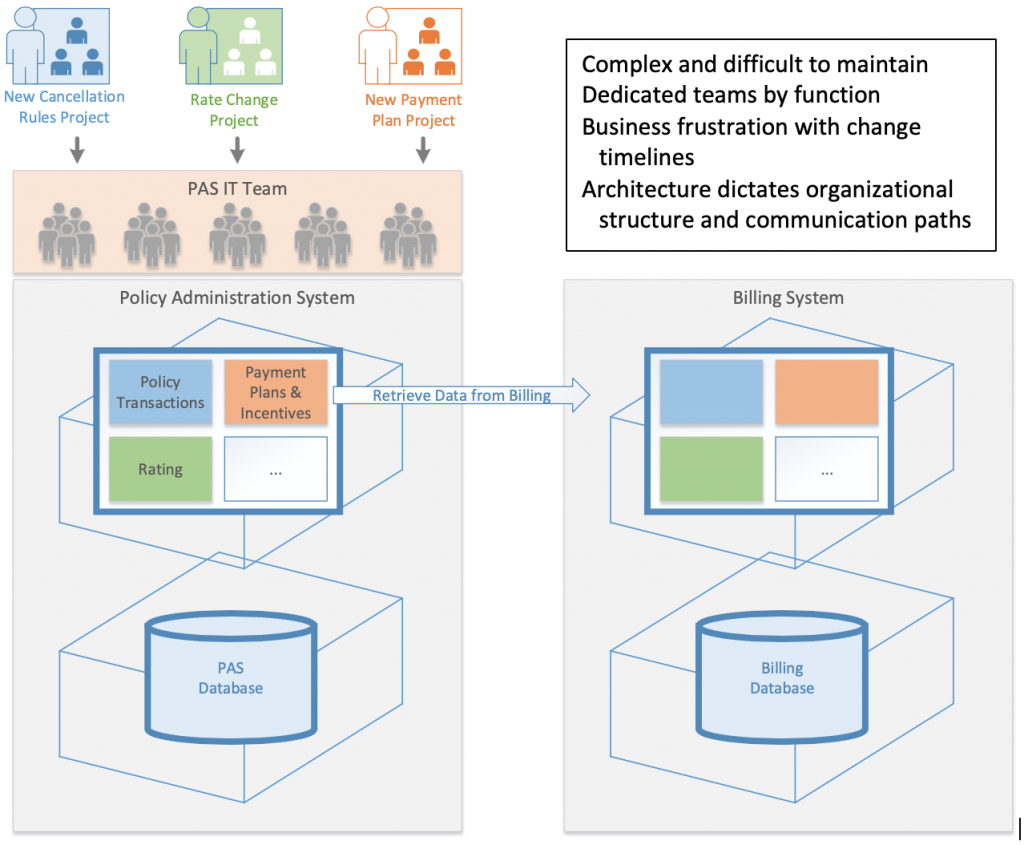

All of this and more works against the effort to become truly Agile. If systems and infrastructures are not loosely coupled as Agile prescribes, it becomes exceedingly difficult to work in an Agile fashion. For example, if a development or support team needs to make changes to a database that is shared by many components, then it needs to coordinate with many other teams. And if the change requires other teams to also make changes as a result, then the whole process can slow or even bog down. And if one of the teams needs to make changes to an application that is large and that is owned by several teams, then such changes need to be carefully coordinated and tested by everyone and that creates dependencies between teams that can greatly delay progress. The bottom line is that these problems are not new, and it has always been difficult to solve them. The following current state illustration typifies the difficulty in maintaining monolithic and fragmented business technology architectures:

Part 2 of this article will discuss a practical and achievable approach that insurers can employ to create a sustainable Agile architecture and organizational structure.

Originally published in

Insurance Innovation Reporter

Read the original article here.